The Exploration ...

The Novel ...

The Discovery

I stumbled onto a national treasure.

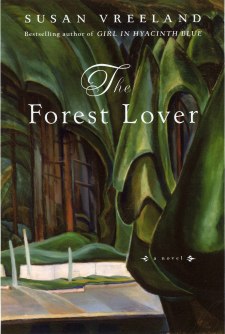

In 1981, on assignment for The Saturday Evening Post to do a travel story on Victoria, British Columbia, I found a rich combination of a Pacific Coast city with a highly visible British heritage, a thriving Native culture and art, and a history as a pioneering outpost. Walking along Wharf Street to photograph the Inner Harbor, I was stopped in my tracks by a reproduction of a painting in a window. A Southern Californian in British Columbia for the first time, as I was, is a person agape at green. Here was a painting of a forest in a myriad of greens--wet, overpowering greens that promised mystery. No earth. No path. No sign of man. Just dense, heavy boughs lying in curves on each other under a corner patch of sky. The foliage itself was the justification for the painting, if a painting needed justification when the love that had been poured onto that canvas was so clear. A courageous individual painted this, I reasoned, one who didn't bow to conventional composition, one whom I wanted to know. I went in.

|

|

Emily Carr, "Cedar Sanctuary," oil, 1942, 91.5x61 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery, VAG 42.3.71. © Vancouver Art Gallery |

The Emily Carr Gallery, once her father's warehouse, introduced me to a woman who brought all the contrasting elements about this city together. Laid out in display were photographs of her on horseback, camping in a caravan in the forest, painting the ruins and totem poles in a Haida village. Here was a woman I'd never heard of, yet her paintings astounded me, her feisty personality amused me, and her independent life fascinated me.

As I became a little familiar with her work, I found it everywhere in Victoria--in other galleries, on note cards, mugs, and T-shirts in tourist shops. Then I began to run across her books. Her stories of her visits to Native villages won the Governor General's Award, Canada's highest literary prize. Intent on "knowing" her, I bought all of them--a large art book of her paintings, her stories, and her personal journals. They were strikingly self-revelatory. Cultivating her sense of alienation from majority society, celebrating her rebellious self, railing against narrow mindedness and provinciality, she had all the makings of a Byronic heroine. It astonished me, therefore, that never had a novelist attempted to make Emily Carr the subject of a work of fiction.

Though she died in 1945, she remains, "a living and vital Canadian presence, a legend, a national treasure."* It is not incorrect to say that a piece of British Columbia is Emily Carr.