Renoir and Luncheon of the Boating Party

|

|

|

|

|

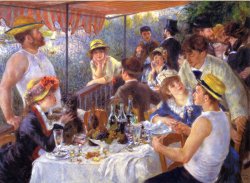

Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, detail, 1880-81.

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

|

Vreeland magically transported me into the wonderful world of Renoir and his models.

I lived there, tasted and breathed the atmosphere. A rich, compulsive read.

--Edward Rutherfurd, author of The Rebels of Ireland, and London

"To my mind, a picture should be something pleasant, cheerful, and pretty, yes pretty!

There are too many unpleasant things in life as it is without creating still more of them."

--Pierre-Auguste Renoir

|

|

|

|

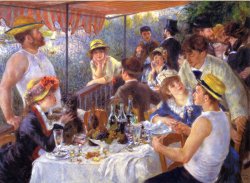

Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-81.

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

|

Besides its extraordinary beauty and sparkling joy, Renoir's well known masterpiece is

somewhat of a miracle on many levels, not the least of which is the contrast between what

it depicts and the "many unpleasant things in life" which preceded it.

|

|

|

|

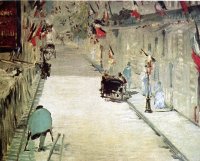

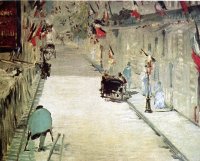

Edouard Manet, The Rue Mosnier Decorated with Flags, 1878.

Paul Mellon Collection.

|

The Time

After the crippling Siege of Paris of 1870 culminating the Prussian War, and France's

humiliating defeat, Parisian insurgents, the Communards, angry with their government's

incompetence, took control of the city in 1871 and declared the end of the Empire.

The popular uprising was put down with draconian cruelty, and the psychological trauma

was felt for decades afterward. To atone for the 20,000 Communards killed in street

fighting or executions, a magnificent church, Le Sacre Coeur, would rise from the Butte

of Montmartre, once the stronghold of the rebellion.

|

|

|

|

Edgar Degas, Aux Ambassadeurs, 1877.

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon.

|

Stiff war reparations were paid in record time, and after six years of economic depression,

by 1880, Paris was exploding with creative energy and optimism. Cafés, café-concerts,

cabarets, dance halls, theaters, hotels, department stores all flourished.

|

|

|

|

Renoir, The Grand Boulevards, 1875.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA.

|

Baron Haussmann's restructuring of Paris begun before the war under Napoléon III

continued, with the aim of opening up the city to create glorious squares and promenades,

building Les Grands Boulevards, making it a showplace, a luxurious and fashionable epicenter,

declaring it the cultural capital of Europe.

|

|

|

|

Renoir, The Loge, 1874.

Courtauld Institute Galleries, London.

|

La Vie Moderne

The setting was ripe for a new society. La vie moderne was born, made possible by

the shortening of the work week. The workers were given their Sundays.

In Paris, the grand boulevards were built for strolling, for mutual observation,

flânerie, looking while being looked at, for posing as one class higher than one's

station. While the promenoirs provided a strolling space for rendezvous of upper

class people at the Opéra,

|

|

|

|

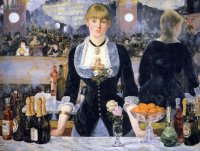

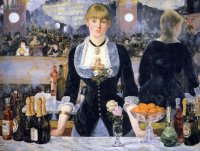

Edouard Manet, Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82.

Courthauld Institute Galleries, London.

|

the Folies-Bèrgere provided its own strolling space, though at a lower social rung.

Department stores and ready-made garments provided the means. The cabarets provided

spectacle--the cancan on stage, the equally wild chahut on the dance floor. Life

was becoming lived in public. "Leisure was a performance, and the thing performed was class." (1)

|

|

|

|

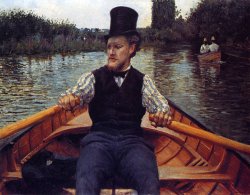

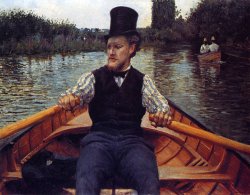

Gustave Caillebotte, Boatman in a Top Hat, 1877-78.

Private Collection.

|

With the building of railroad lines to the countryside just beyond the suburbs, Parisians

could enjoy their Sundays in a number of riverside villages to the west of Paris.

|

|

|

|

Gustave Caillebotte, Périssoires, 1878.

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes, France.

|

The possibility to rent a boat (un canot) for an hour or an afternoon and row where

one pleased, to stop to picnic on the lawns of former private châteaux, gave people a

sense of freedom. In this new age, anyone could become un canotier. Boating costumes

could be had inexpensively. Songs and vaudeville extolled the birth of recreation, and the

new painting portrayed it.

Impressionism

The goals and achievements of Impressionism flew in the face of traditional art instruction

provided at l'École des Beaux-Arts and supported by the Académie which organized

the official government-sanctioned yearly show of new work, dubbed the Salon, but held at

the Palais de Champs-Élysées.

|

|

|

|

Edgar Degas, Women on a Café Terrace, Evening, 1877.

Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

|

Impressionism signaled a virtual overthrow of academy dictates in subject matter, style,

and methods. Rather than subjects taken from history, classical mythology, or the Bible,

Impressionists sought to portray their own time in all its variety and vibrancy.

|

|

|

|

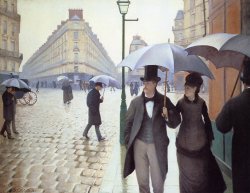

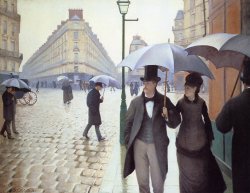

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street, Rainy Day, 1877.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

|

In an essay of 1876, "The New Painting," critic Edmond Duranty wrote: "Farewell to the human

body treated like a vase...Farewell to the uniform monotony of the bone structure...What

we need are the special characteristics of the modern individual--in his clothing, in social

situations, at home, or on the street...Eliminate the partition separating the artist's studio

from everyday life. Make the painter come out of his sky-lighted cell...and bring him back among

men, out into the real world." (2)

|

|

|

|

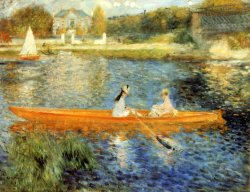

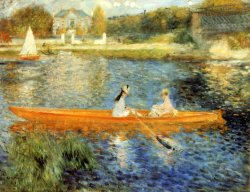

Renoir, The Seine at Chatou, 1881.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA.

|

In terms of style, Impressionists sought to capture the fugitive effects of light on a subject

by softening the edges, often painting outdoors, en plein air, without benefit of

preparatory drawings. Technique involved the juxtaposition of patches of contrasting color

which the eye would blend.

|

|

|

|

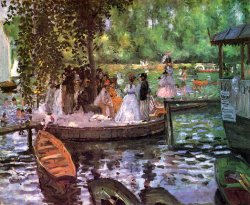

Renoir, Boating on the Seine, 1875.

The Trustees of the National Gallery, London.

|

Jules Laforgue, the figure at the rear left in Luncheon of the Boating Party,

distinguishes between the academic

painter's treatment of light and the Impressionist's: "The academic painter sees nothing but

white light spreading everywhere, whilst the Impressionist sees it bathing everything not in

dead whiteness, but in a thousand conflicting vibrations, in rich prismatic decompositions

of colour...and the eye of the master will be the one which will discern and render the keenest

gradations and decompositions." (3)

One might say the Impressionists favored color over line.

|

|

|

|

Renoir, Portrait of the Actress, Jeanne Samary, 1877.

Pushkin Museum of Art, Moscow.

|

Renoir

Though Renoir was a worshipper of light as well as were Monet and Pissarro, he didn't like

painting being reduced to the science of optics. He eschewed theories. "I see something. I paint it."

At the time he embarked on Luncheon of the Boating Party, he was cultivating, perhaps

juggling is the better word, two styles--the Impressionist technique of feathery touches of

unblended color, showing the painter's brushwork, and the smoother, blended style of the

classical painters he admired: Rubens, Ingres, Boucher, Watteau, Fragonard. The former style

suited paintings done for himself, often outdoors; the latter suited the portraits commissioned

by members of the grand bourgeois. Though portraits provided the majority of his income, at this

time in his life, his interest was more passionately directed to painting genre scenes of modern

life, for which the Seine provided the perfect setting.

|

|

|

|

Renoir, The Rowers' Lunch, 1875.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

The setting is Maison Fournaise.

|

The Setting

Asnières, Argenteuil, Bezons, Chatou, Bougival--all river towns, attracted Parisian

day-trippers and painters by the droves.

The railroad line to the west of Paris crossed the Seine some hundred yards south, downstream,

of Ile de Chatou, the narrow island in a string of connected islands separating the river

into a commercial channel and a pleasure boating channel. There, La Maison Fournaise was

situated. It was one of many guinguettes, riverside restaurants offering music, sometimes

dancing, and in the case of La Maison Fournaise, the rental of various types of rowing craft.

|

|

|

|

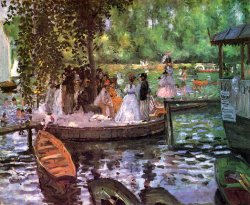

Renoir, La Grenouillère, 1869.

National Museum, Stockholm.

|

Downstream, La Grenouillère was the raucous swimming area with a large floating

dance floor painted several times by both Renoir and Monet. Further downstream, the large

establishment, Bal des Canotiers, held dances twice a week.

|

|

|

|

La Maison Fournaise et la Seine, Chatou, circa 1890.

late 19th century postcard.

|

Renoir had known the Fournaise family for ten years. The popular restaurant attracted

performers, writers, and painters, notably Monet, Degas, and De Nittis. In years following

Renoir's stay there, Maurice Réalier-Dumas, André Derain and

Maurice de Vlaminck painted there. Here was ample subject matter among serious as well as Sunday

afternoon "canotiers," boaters. And here Renoir set his masterpiece.

|

|

According to Renoir scholar John House, "The theme of canotiers was inextricably linked,

in popular mythology, with narratives of amorous interchange and sexual intrigue." (4)

All the more intriguing for a painting, or a novel.

|

|

|

|

Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, detail, 1880-81

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

|

The Painting

Renoir wanted less to tell a narrative in his paintings than to simply present a picture of

a time and place and group of people. In the case of Luncheon of the Boating Party,

although we can see interactions between the figures, we don't know their relationships or

the content of their conversations.

|

|

|

|

Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, detail, 1880-81

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

|

At the end of his life, Renoir told his son Jean, "What is important is ...to avoid being

literary and therefore to choose something that everyone knows--better still, to have no

story at all...Under Louis XV, I would have been obliged to paint subjects. What seems to

me the most important thing about our movement is that we have freed painting from the

subject. I can paint flowers and simply call them 'flowers' without their having a story." (5)

|

|

|

|

Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, detail, 1880-81

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

|

That refusal to supply a narrative makes the painting intriguing to comprehend. All we

see is that clothing and poses suggest different classes. Interactions crisscross each

other on the terrace, but no relationships are definitive.

That leaves the field wide open to the imagination of the viewer--and the novelist.

|

|

1 Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, as quoted in T.J. Clark,

The Painting of Modern Life, p. 204.

2 As quoted in Charles Moffett, "An Icon of Modern Art and Life," in Impressionists on the Seine,

The Phillips Collection, 1996, p. 149.

3 As quoted in T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life, p. 16.

4 John House, The Promenade, p. 73.

5 Jean Renoir, Renoir: My Father, pp. 68, 179.

|

|