|

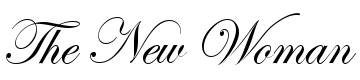

"The thrill and exhilaration of mastering control of a bicycle would be matched by the sense of accomplishment a woman could experience in mastering control of her own personal destiny," wrote the suffragist Frances Willard in How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, 1895. Learning to stop, slow down, speed up, turn, stop, start, and steady oneself had their corollaries in life. Equilibrium on a machine could give a woman equilibrium of thought and action.

Of course, there were vocal objectors, even among women. An editorial declared, "At least half the interest of one sex in another arises from their respective dependent and protective positions. When a lady velocipedes, she destroys all this kind of subtle interest." Into the fray rode the indomitable Susan B. Anthony who wrote in her periodical, Revolution, "Bicycling [has done] more to emancipate woman than anything else in the world...[A woman awheel] is the picture of free untrammelled womanhood."

|

|

|

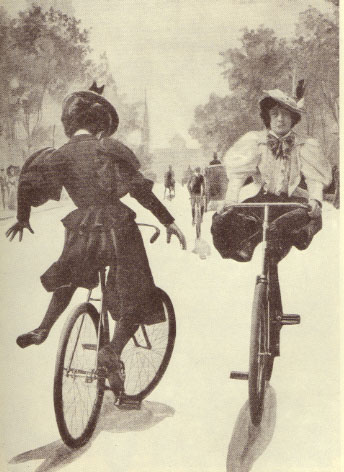

Ladies Standard, June 1897.

|

|

|

Though Clara doesn't say it outright in her letters, she knows that the wheel within the wheel is the revolution of roles and limitations on women, manners and morals. In one sense, it's her transport into the realm of The New Woman.

Astride the bicycle seat or not, the new urban woman of the decade before and after the turn of the century craved adventure and freedom. Typically, she was somewhat educated, made her own living independently, and engaged in the life and culture of the city as much as her income could provide and her tastes dictate, thus inventing for herself a meaningful life beyond the domesticity of the traditional family home.

|

|

|

View of the Glass Room with Women at Work. Art Interchange, Oct., 1894.

|

|

|

In the late nineteenth century, decorative arts of stained-glass work, pottery, and needlecraft furnished a polite way for many middle-class women to earn their living. Art was as ladylike as teaching, so she would not be scorned for undertaking a profession in the arts. The young woman who sold her crocheted doily to the Women's Exchange came away with more than coin in her pocketbook. She had the satisfaction of having turned her ability to cash. Even so, the receiving of payment, weekly or by piecework (curling feathers for hats, embroidery, tapestry), bestowed no greater joy than having been addressed in a business-like manner as Miss Driscoll or Miss Northrop.

|

|

|

Making a Cartoon at The Tiffany Studios. Art Interchange, Oct., 1894.

|

|

|

The New York woman, whether or not originally from a small town, had, by virtue of observation, more knowledge of the world, and she knew that she could do pretty much what she pleased, if it was done with a certain dash. For example, a group of women did the painting on the ceiling of a theater, working on scaffolding as if they were day-laborers, albeit wearing men's trousers underneath their skirts. A girl in a small town would have been scorned for doing such work, but in New York, it was more likely to be accepted.

|

|

|

Tiffany Girls at Midland Beach, Staten Island, New York, 1905. From the collection of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida, © Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation, Inc.

|

|

|

Out of shared work came shared friendships between similarly situated women, relationships that replaced family ties, offered camaraderie, opportunity for sharing opinions, tolerance, consideration in illness, sympathy in joy and sorrow, and the possibility of borrowing money from one another when necessary. Such women often shared rooms in boardinghouses, or rented a cubby hole of space just for herself, as Alice Gouvy did. It may have been impossibly small, but it was hers, and it fed her sense of independence.

|

|

|

Tiffany Girls Feeding Each Other: Alice Wilson, Nellie Warner, Theresa Baur, Annie Tierney, and Mary McVickar, c. 1905. From the collection of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida, © Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation, Inc.

|

|

|

The New Woman was a vibrant figure in late nineteenth century fiction, providing a model for women in cities to imagine becoming themselves. Fictional New Women helped to diminish cloying associations with the Victorian "lady artist," associations which presented her work as amateur, sentimental, and genteel. Earlier nineteenth century novels characterized women alone in cities as friendless, forlorn, and sexually vulnerable, as Stephen Crane presents in his 1893 naturalist novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. Unlike such morality tales admonishing young women that their foolish infatuations might disqualify them from marriage, New Woman fiction presents Bachelor Girl, Gibson Girl, and Bohemian Girl heroines as plucky, adventurous, in command of humor, focusing their romanticism on meaningful work rather than on love. This popular writing was assimilated by eager audiences, perhaps even by some of the Tiffany Girls, and gave direction and approbation to paid work in the arts or beyond.

I am grateful to the following sources for material on this page: "Women Bachelors in New York" and "The New York Working Girl," by Mary Gay Humphreys, Scribner's, October, 1896; and American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Creation of a New Century, by Christine Stansell, Henry Holt & Co., 2000.

|

|

|