|

|

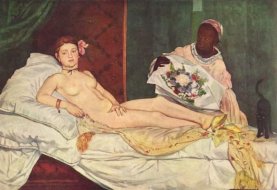

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863.

|

These stories were written before, between and after my three novels about paintings and painters.

I thought of them as studies of the lives surrounding the painters.

Just as painters do studies of details from life, that is, from live models, in the process of working up a large and complex canvas, so were these stories my studies of details of lives that, taken together as the large canvas of a story collection, might show the complexities and richness of people whose lives are lived close to art.