|

|

|

|

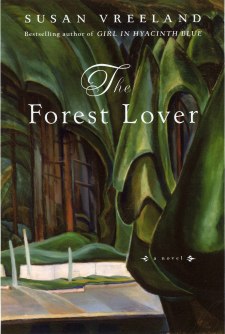

Reviews of The Forest Lover |

|

|

Publication date is February 9, 2004

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

PUBLISHERS WEEKLYThe Canadian artist Emily Carr (1871-1945) could be a feminist icon. Spirited and courageous, inspired by an inner vision of "distortion for expression" and by a mission to capture on canvas the starkly fierce totem poles carved by the Indian tribes of British Columbia, Carr endured the disapproval of her family and of society at large until her belated vindication. One of the pleasures of this beguiling novel based on Carr's life is the way Vreeland (Girl in Hyacinth Blue) herself has acquired a painter's eye; her descriptions of Carr's works are faithful evocations of the artist's dazzling colors and craft. No art schools taught the techniques that Carr felt suitable to the immense, rugged landscape of British Columbia. Moreover, when she ventured into isolated tribal villages and befriended the natives, braving physical discomfort and sometimes real danger, she was accused of "unwholesome socializing with primitives." Drawing on Carr's many journals, Vreeland imagines her experiences in remote areas of B.C. as well as in Victoria, Vancouver and (briefly) France. There are few dramatic climaxes; instead, Vreeland emphasizes Carr's relationships with her rigidly conventional siblings and with her mentors and colleagues. She vividly describes the obstacles Carr faced when she ventured into the wilderness and in her periods of near poverty and self-doubt. A fictitious French fur trader introduces a romantic element, which may offend purists. Much of the suspense comes through Carr's affectionate relationship with a real woman, Sophie Frank, a Squamish basket maker who loses nine children to white men's diseases. Adding to Sophie's emotional desolation is the torment introduced by inflexible Christian dogma that alienates tribes from their native traditions and spiritual beliefs. Vreeland provides this historical background with the same authoritative detail that she brings to the Victorian culture that challenged Carr's pioneering efforts. Her robust narrative should do much to establish Carr's significance in the world of modern art. Forecast: Vreeland's sizable audience should guarantee this book an early place on the charts. NEW YORK NEWSDAYTo her local newspaper, she was "a lady painter who had once shown promise" but had "thrown reason to the winds" and "outraged nature with her colors" and made a "sorry attempt to eclipse the Almighty by producing bizarre work." To the Indians of Canada's west coast, she was "Hailat, Person with spirit power in her hands." Emily Carr took both as badges of honor. In The Forest Lover, Susan Vreeland, author of two bestselling novels of the art world--The Passion of Artemisia and Girl in Hyacinth Blue--creates an Impressionist canvas of Emily Carr's life, based on fact and imagined into what Carr might call "something bigger than fact: the underlying spirit, all it stands for..." The facts: Carr, born in 1871 in Victoria, B.C., studied art in England and was a competent watercolorist (instruction in oils being reserved for men). She made a meager living teaching art classes, but her passion was for the wild--the vast primeval forests and Indian civilization vanishing around her. She studied painting (oils this time) in pre-World War I France, discovered Impressionism and the Fauves, returned home and really painted, to the horror of the critics (see above). Like most independent women, she was seen as eccentric, and ignored. She finally achieved national (if not local) recognition when, at 57, she was invited to show her work in the National Gallery in Ottawa, where a critic declared her art "as big as Canada itself." (Emily was "thrilled purple.") After two heart attacks and a stroke, she kept on painting, saying, "Don't pickle me away as done!" She died in 1945. On this framework Vreeland hangs her story of Carr's spiritual and artistic journey. She fleshes out Carr's friends--Sophie, a Squamish basket maker; Harold, son of missionaries, persecuted for his love of Indian ways--and even imagines for Carr a romance with a French fur trader (well, why not? Carr would no doubt think it "dandy fine!") Resonating like drumbeats in the forest are Vreeland's renderings of Carr's intrepid journeys deep into the wilderness, alone, armed with easel and paints, in search of the wild and the disappearing culture of Haida, Tlingit, Kwakiutl and others--the totem poles and decorated canoes, long-houses and menstrual huts. Raven and Wolf and Eagle and Dzunukwa the monster woman. Their spirits, and Carr's leap from her canvases--and from the page. Vreeland, as the Squamish would say, has made strong talk. January 25, 2004 BARNES AND NOBLE REVIEWSusan Vreeland's third novel (after "Girl in Hyacinth Blue" and "The Passion of Artemisia") again brings to light a prominent female artist, this time modern Canadian painter Emily Carr. As imagined here by Vreeland, Carr struggles against turn-of-the-century Victorian codes that dictated both how a lady should act and how art should rendered and evaluated. In embracing the rapidly disappearing indigenous cultures of British Columbia, Carr created bold, Impressionist paintings that horrified the public as much as those of her male French counterparts. It was only belatedly (though still in her lifetime) that her art was embraced. In this richly imagined telling of Carr's life, Vreeland creates a fascinating cast of characters, from the indigenous people Carr befriends to her own sisters who cannot understand her passions or her paintings. Most memorable is her friendship with a mentally disabled man, Harold, who finds peace in Carr's paintings, which remind him of his own troubled childhood as the son of missionaries. Filled with vivid detail and gorgeous descriptions, "The Forest Lover" is a lush, rich novel that will not disappoint fans of Vreeland's earlier efforts. MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINELSpirited adventure Vreeland sketches Canadian artist's wilderness quest by Catherine Parnell, January 17, 2004 Susan Vreeland has done it again. Her latest offering, "The Forest Lover," serves us a speculative, romantic account of the life of Canadian artist Emily Carr. Vreeland, no stranger to art ("Girl in Hyacinth Blue," "The Passion of Artemisia"), throws her writerly weight into Emily Carr's life in British Columbia in the early 20th century, a world Carr reviled and forsook periodically for that of the forest primeval, populated with spirits and the Indian peoples of the Northwest Coast. With the publication of "The Forest Lover," Carr's work--and by extension, Canadian art--will receive the notice it has long deserved outside Canada, and with it will come a fictionalized encounter with one woman's struggle to follow her passions. Writing with insight and authority, Vreeland summons Carr from beyond the grave. The intimate connection between writer and subject deepens as the novel progresses, yet Vreeland's authorial tone is as quiet as an individual in a museum. Emily Carr grows in this novel as she grew in life, with the added dimension of Vreeland's imagination. Feisty and driven by an inner passion and vision, Carr traveled the harsh landscape of British Columbia to isolated tribal villages at a time when primitive was perjorative and socializing with Indians (the term Carr used, and the term Vreeland wisely sticks with in her historical novel) was frowned upon, if not forbidden. Carr's early art, dominated by natural and Indian themes, was nearly ignored. Carr left Canada to study in France, and on her return to British Columbia, she devoted herself to capturing a way of life that was rapidly disappearing, thanks to missionaries and art poachers. Carr's mission was to feel the "greatness of Canada in the raw." The image of a woman lifting swaths of skirt to relieve herself in the wild or fending off ravenous mosquitoes as she painted adds realistic grit to the novel. Obsessed with Indian villages, houses, potlatches and totem poles, Carr drove herself beyond the limits of respectability and propriety, past "narrow lives all tickety-boo without a doily out of place" to immerse herself in tribal worlds twisted by Christian dogma. Nowhere is this dissonance more evident than in Carr's relationship with Sophie Frank, a Squamish basket weaver whose children don't live to puberty. In a sisterly moment, Sophie paints reddish brown tamalth across her cheek to make her strong to "have babies" and Carr paints her own face, murmuring an urgent prayer to "You Who Dwell in the Forest" to "Give power to my brushes so I can create something true and beautiful and important." As Carr paints in the wild, Sophie buries one child after another. Her struggle to buy Christian gravestones for her children--despite the presence of the totemic Ancestor outside the graveyard--mirrors Carr's determination to paint. Each woman seeks to honor the dead in the face of cultural conflict. Vreeland's exacting descriptions of Carr's art fly from the page. An encounter with a Dzunukwa totem with its exaggerated smile transcends conventional notions of art as Carr reminds herself: "Distortion for expression." Dzunukwa becomes a portrait of shapes that express something personal and compelling, so authentic that a group of Indians recognize Carr as a hailat, "a person with spirit power in the hands." Carr's placement beside the Canadian artists known collectively as the Group of Seven established the significance of her work in the Canadian world of modern art. Some in that world may be enraged over Vreeland's interpretive liberties, but in the end they will see that Vreeland has done in her novel precisely what Carr did in her paintings--urge us "to drink in the forest liquids" and "sing the forest eternal" through inspired vision. KIRKUS REVIEWSFictionalized biography of painter Emily Carr by bestselling Vreeland (Girl in Hyacinth Blue, 1999; The Passion of Artemisia, 2002) Carr (1871-1945) was perhaps the first Canadian woman artist to achieve international recognition, partly thanks to her studies abroad (in America, London, and Paris) and partly thanks to her association with the famed Group of Seven, a Toronto-based salon of painters who revolutionized Canadian art. In her third historical, Vreeland adds some invented characters and situations, but for the most part offers a faithful account of Carr's career. Born in Victoria, British Columbia, she lost both of her parents early in life and was raised by her domineering elder sister Dede, who disapproved of Emily's interest in painting and tried to prevent her from enrolling in art school. Because of an interest in Native American art that was unusual for her times, Carr lived for a while among the Squamish Indians of Vancouver Island [sic], studying their crafts and rituals. There, she met Sophie Frank, a Squamish basket weaver who became both friend and inspiration, as well as Claude Serreau, a French-Canadian fur trapper who was briefly Carr's lover. The Indian themes that dominated her early work were not well received in Canada, so in 1910 Carr traveled to Paris to immerse herself in the new styles that were coming into vogue among modernists. In France, she befriended New Zealand painter Frances Hodgkins, with whom she spent a happy summer working in the countryside, but she found as little encouragement in Paris as she had in Vancouver. After a year, she returned to Canada and dedicated herself to painting the Native American villages, houses, and totem poles that were fast disappearing. Eventually, she mounted an exhibition at the National Gallery in Ottawa that established her as one of the leading artists of her day. A sensitive, sober account of an interesting woman and her times, narrated with respect for the factual record and a minimum of heavy breathing. BOOKLISTIn her last novel, best-selling author Vreeland fictionalized the life of Renaissance painter Artemisia Gentileschi. She now presents a speculative portrait of the intrepid and too little known British Columbian painter Emily Carr (1871-1945), older sister-in-spirit to O'Keeffe and Kahlo. Awareness of Carr's extraordinary life and unprecedented paintings of Canada's magnificent western wilderness and the carvings and totem poles of the region's native peoples is increasing thanks to renewed appreciation for Canada's Group of Seven, a circle of male painters also committed to celebrating their country's pristine natural beauty. But Carr, working in painful isolation, was way ahead of them, and her passionate quest induced her to break every rule of conduct for a Victorian-era white Christian woman. Vreeland couldn't have chosen a more vital, compelling, and significant subject, although she does romanticize Carr's incredible life nearly to the point of superficiality. Even so, her dramatic depictions of Carr's daunting solo journeys, arduous artistic struggle, persistent loneliness, and despair over the tragic fate of the endangered people she came to love truly are provocative and moving. And Vreeland is to be commended for introducing Carr to the wider audience she so deserves.

by Donna Seaman

THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR"I'm dreadfully hankery for forest" Canadian Painter Emily Carr was drawn to native culture decades before her countrymen saw its value. Emily Carr once said, "Nobody could write my hodge-podge life but me." With self-effacing humor, she claimed that biographers couldn't "be bothered with the little drab nothings that have made up my life." To Susan Vreeland, who's quickly become America's most popular biographer of famous artists, that must have sounded like an irresistible challenge. Her bestselling "Girl in Hyacinth Blue" followed the life of a single Vermeer painting from the 20th century back to its creation in 17th-century Delft. The feminist theme laced delicately through that novel's closing chapters became the heavy-handed impulse of her next book, "The Passion of Artemisia," about the Renaissance painter Artemisia Gentileschi. Now, with "The Forest Lover," her story of Emily Carr, Vreeland has found perhaps the most appropriate venue yet to express her own exuberant feminism and spirituality. What more, by immersing herself in Carr's extensive writings, Vreeland has picked up the tenor of the painter's language--her eclectic mysticism, emotional devotion, and single-mindedness... Vreeland picks up the story when Emily is 33, already a confirmed eccentric, an embarrassment to her prim sisters, who can't fathom why she wants to wander around the forest looking at pagan relics and "socializing with primitives." To Carr, the attraction is profound, though vague: She hopes to "discover what it is about wild places that call to her with such promise." ...The novel is made up of little episodes, sometimes only thinly connected, that hopscotch through Carr's life. We land on her efforts to teach prissy women how to paint, a trip to France that introduced her to Post-Impressionism, arguments with her aesthetically dim sisters, her time as a landlady, and an affair that Vreeland invented to dramatize Carr's sexual ambivalence. Carr's strangely childlike personality comes through well--her guilelessness, her straightforward devotion (or rejection), the enthusiasm that outstrips her diction. Asked how she can paint the wind, Carr answers, "By making the trees go whiz-band and whoop it up." ...Ultimately two very different friends of Carr emerge as more interesting characters than she is. One is Harold, a mentally impaired man who was brutalized as a boy for his interest in the Indians, and the other is Sophie, a Squamish basket maker who suffers the death of one child after another. Both these people, the kind of strange oddballs that Carr sympathized with, live stretched in painful suspension between cultures that won't accept them. Harold is eventually driven insane by his guardian's insistence that he abandon the Indian songs that animate him, and Sophie is wracked with guilt for alternately betraying her ancestral god and her Christian God. These are sensitive portraits, drawn with all the necessary pathos, and they indicate the deeper mysteries of faith intimated by Carr's paintings. But through most of this novel, Vreeland seems unwilling to mix the primary colors on her narrative palette to produce anything equally suggestive or subtle. Only the final chapters rise to that challenge and provide some truly beautiful, stirring writing. Carr had to be patient for decades, waiting for critics to recognize the power of her dark, lush work. Readers of "The Forest Lover" won't be disappointed for exercising the same perseverance. by Ron Charles JANUARY MAGAZINEAppreciative Appropriation Historical novelists have a lot of decisions to make. Not just about what story to tell or even how to tell it, but about which slices of a life need to be illuminated to provide readers with the fullest, richest impact. Skillful novelists know just how to make those slices: the decisions they make are good ones. Less skillful novelists, not so much. It's only one of the things that sets the two groups apart. Clearly, Susan Vreeland is a skillful novelist. More: relatively early in her writing career, Vreeland has discovered her oeuvre. The author of "Girl In Hyacinth Blue" and "The Passion of Artemsia" knows her way around the art world. She understands the difference between looking and seeing, knows the subtleties of burnt umber and sienna. And, most important of all, Vreeland truly gets the off-kilter way that artists view the world. Artists aren't like other people. Vreeland embraces this. And, in a very positive way, exploits it. Vreeland's special view is as apparent in her most recent novel, "The Forest Lover," as it has been in any of her work to date. Here Vreeland slices the life of Canadian artist Emily Carr. Carr's rich, vibrant paintings of the forests of the West Coast and the native totems she wanted to preserve through her art caused shock and outrage when first exhibited and eventually helped to secure her place as one of the most important of a small group of internationally known Canadian painters. In "The Forest Lover" Vreeland's creative decisions are myriad and interesting. She's chosen to slice Carr's life down to the artist's most productive years: between about 1904 when the painter was still very much finding her style, through to 1930 when the Canadian art establishment finally caught up with Carr and recognized that her oils were worthy of attention. From Carr's perspective, at least as depicted by Vreeland, with her first group show in Toronto, the artist felt she had finally arrived. At least, she'd arrived enough that she no longer had to dismantle her fence to make stretchers for her canvases and she no longer had to breed sheepdogs and make pots to pay her mortgage. Though Vreeland has introduced strongly fictional elements in "The Forest Lover" -- the whiff of a romance with another painter in France and a Quebecois trader in British Columbia, for instance -- for the most part, the author gives us beautifully reconstructed facts. It could be argued that the fictional romances Vreeland has included in "The Forest Lover" serve to give emotional balance to Carr's only true and documented romance: the one she enjoyed with the rugged wilderness of the northern coast of North America. In the early portions of the book, we witness Carr's frustrations with the limits of her talent and her materials: she is unable, at first, to bring forth what she feels in her heart. Sketching in watercolor, she laid in the main shapes. She squeezed her brush dry to lick up excess paint above the beak to lighten it where it reflected the sky. The eye had to be fierce. She darkened the heavy bone above it. It was still too tame compared to the strangeness and wildness of that glowering totem. She tried to be bolder and still be accurate, but how could she with watercolor? Those British academicians passing for artists, squeezing their brushes at the ferrules, had crippled her, made her work timid. If only she could talk with someone who knew how to make paintings express feelings. Carr's major limitation proves to be entirely material: Like the proper Victorian girl she was, Carr was permitted only watercolors. The oils with which she would create her most luminous and memorable works would not become part of her creative arsenal until she went to France to study in 1910. In France she learns more than proficiency with oil paint: she relearns how to see: Before her a pale sienna strip narrowed in the distance, lined by white rectangles. The sensation was eerie. Where there had been hayricks when she walked into Héloïse's cottage, now there were giant ochre blocks. Near them stood three connected trapezoids with defined planes, on four angled cylinders in Vandyke brown. It might be a horse. It didn't matter what it was. It was more interesting as shapes and planes. On the way home, shapes and planes overwhelmed her as the only reality. She breathed hard. This she could use to paint totems. One of the things that "The Forest Lover" can approach only obliquely -- due to scope -- are the questions of appropriation and misappropriation that have, in many ways, prevented Carr from taking her full place in Canadian history. Carr's work was viewed controversially throughout her lifetime and has, for quite different reasons, continued to do so since her death in 1945. There are those within the Canadian art establishment who have accused Carr of appropriating native images for her own reasons. Others have suggested that, instead of painting the native images she appreciated so deeply, Carr should have stood up for British Columbia's indigenous people and corrected the wrongs that she knew were being done. Yet stand, as I have done, in a gallery filled with the work of Emily Carr. Take in the majesty of the giant canvases: the perfection of the artist's virgin forests, the enduring dignity of her totems. And remember that the very best of them were painted at a time when their very creation was an act of rebellion: a shunning -- some would have said a shirking -- of convention. Years before Frida Kahlo, Georgia O'KeeFfe and Tamara De Lempicka fought their own battles to become "women painters," Carr moved mountains of tradition to spend weeks in the wilderness recording with her heart and brush at a time when women in North American couldn't vote and many couldn't own property or hold a bank account. In "The Forest Lover" Susan Vreeland gives us an intimate introduction to a quietly courageous and deeply talented artist. Has she appropriated here? Perhaps. But if so, Vreeland's motivations could not have been far different than those of the artist she writes about. Vreeland brings us Carr's story with love and appreciation and the desire to lovingly present the truth as she sees it. Somehow that's enough. by Linda Richards, editor of January Magazine. SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNEThe Life of the Artist Local author Susan Vreeland neatly paints a fictional Emily Carr, "The Forest Lover." Emily Carr, Canada's beloved painter and writer who died in 1945 at the age of 74, lives on not only in her paintings, but in her writings and series of memoirs, and in the many books, journals, diaries, letters, essays, quotations and biographies written about her life and her work. She won the Governor General's Award, Canada's highest honor for literature, for her autobiography, "Klee Wyck," in 1941. Now we have Susan Vreeland's "The Forest Lover," a novel fictionalizing the life of this formidable artist. Mythologized to icon status since her death, Carr is Canada's most famous female artist, lauded on a par with Frida Kahlo and Georgia O'Keeffe. An important artist in the late 19th-century crisis of cultural authority, Carr might have been one of the Gorilla Girls, a modern underground movement of female artists protesting male dominance in the art world... "Deep down", writes Vreeland, "we all hug something. The great forest hugs its silence. The sea air hugs the spilled cries of sea birds." Chapter titles are named for trees, animals or birds, reflecting a moment in the legacy of that creature or thing to make a metaphorical or anthropomorphic statement. Each section produces a surprise package of lush passages, vivid and dense as the Northwest forest and terrain they describe. Carr, who felt God in the spaces between trees, would likely approve... Today, Carr and her art are legendary, and in "The Forest Lover," Susan Vreeland, author of "Girl in Hyacinth Blue" and "The Passion of Artemisia," gives us a truth-seeking Emily Carr in a background of monumental and fearsome beauty. by Marie Giordano ALBUQUERQUE JOURNALNovel Follows Painter's Colorful Life ..."The Forest Lover" begins in British Columbia but as the detailed maps that are the endpapers of the book suggest, the story ranges thousands of miles along the coast and into villages sometimes abandoned because of Christian conversion, sometimes still-vibrant pockets of potlatch customs... Vreeland portrays Carr as a friend to diverse people and the novel incorporates details of the time in an unobtrusive manner. One incident, in which her father had assaulted her, seems almost too modern to be effective and yet is integral to the relationships Carr cultivates with men and women throughout the narrative. Vreeland writes in a fluent style dividing the book into 44 short chapters named (with few exceptions) for natural features of the Northwest wilderness: Raven, Wolf, Salmonberry. Vreeland explains in her afterword that "As she (Carr) wanted to paint the spirit of a thing, so have I wanted to offer the spirit of her courageous and extraordinary life." After first visiting the Emily Carr Gallery in 1981, Vreeland continued to research the artist's life. She followed in Carr's footsteps through the same countryside, talking with people whose relatives remembered her. ...The black-and-white drawings that introduce the five parts of the book only hint at the power of the work with which Carr disrupted the expectations of her time. "The Art of Emily Carr," first published in 1979 and written by Doris Shadbolt, curator of the Vancouver Art Gallery for 25 years, recently has been re-issued--it's a vital companion book to Vreeland's well-written and energetic novel. by Barbara Riley BOSTON HERALDEditor's Choice Oh Canada! Here the author of "Girl in Hyacinth Blue" and "The Passion of Artemisia" turns her attention to Emily Carr, a groundbreaking painter of landscapes and more in Victorian British Columbia. This fully realized portrait of a vital woman is enlivened by accounts of Carr's spunk and adventures, and enriched by Vreeland's understanding of the artistic mind. review by Rosemary Herbert DENVER POSTNorthwest artist's emergence at core of epic Long before British Columbia was a trendy runaway spot for relocated Californians and whale-watchers, it was lush emerald habitat for what would become the Squamish Nation in 1923. These descendants of Vancouver's indigenous people endured Francis Drake in 1579, British colonialists in 1858, the Indian Act of 1884 (to outlaw their native customs) and more - a cornucopia of abuse at the hands of Caucasian intruders. In the face of ignorance that labeled them "no better than wild animals," the Squamish clung to a spirit of civility and a hope for peaceful resolution. Within this swirl of injustice and change, renowned Canadian painter Emily Carr (1871-1945) slowly, painstakingly found an artistic vision and - eventually - a level of success that opened doors for other women painters such as Georgia O'Keeffe and Frida Kahlo. In the evolution of Carr and the Pacific Northwestern region she loved, San Diego-based author Susan Vreeland found the heart of her third and latest historical epic, "The Forest Lover." The story opens in 1906, as the 35-year-old artist and her controlling older sister, Dede, return to Carr's birthplace of British Columbia. After sampling the world, Carr rediscovers her homeland and the native people who live there. Carr's sister disapproves of her affectionate and respectful relationship with the Squamish locals. But the painter is influenced and inspired by her friendships, especially with long-suffering native artisan Sophie Frank, captured here: "Sophie lifted the cloth cover on a shallow basket cradle hanging from the ceiling," Vreeland writes of their early interactions. "Emily peered at the small face, so wrinkled it took something right out of her. "'No worry. He grows fat by and by,' Sophie stroked his cheek, inviting Emily to do the same. Emily shifted her bundle of clothes to one arm and touched the baby's brown skin, so smooth and cool it sent a tingling up her fingers. Sophie set the cradle in motion. 'Three live babies. Four dead ones. I show you."' Like the colors on her palette, Carr's emotional canvas is enriched by awareness. Inspired by Sophie, a sensual French lover and other eccentric characters woven into the fabric of her new life, she begins to capture the images of the forest and the people within it. When her work is not well received by a stilted artistic community, Carr makes a creative pilgrimage to Paris, despite her sister's attempts to stop her. But even Paris proves frustrating and ill-advised. So she returns to British Columbia and the destiny that awaits her. Vreeland, whose grandfather was a painter, has taken some poetic license with Emily Carr's biographical essence in this fictionalization. But according to experts, she hasn't lost track of the artist's purpose or personal core. She has pieced fact and fiction together with such tender deliberation, minor enhancements are difficult to discern. Beyond the obvious biographical elements, Vreeland also captures the flair and flavor of the Pacific Northwest - still heavily influenced by history and natural geographic elements. "The Forest Lover" is a well-researched snapshot of British Columbian history and a spotlight on a region still underexplored. Fans of Vreeland's previous popular novels, the New York Times best-seller "Girl in Hyacinth Blue" and "The Passion of Artemisia," will appreciate yet another memorable personality respectfully portrayed. Readers new to Vreeland's understated but vivid storytelling will be eager to explore what's come before. by Kelly Milner Halls THE DAILY NONPAREIL"Forest Lover" works to preserve culture through art. ...Susan Vreeland traveled to British Columbia to get a feel for the life that Emily Carr lived, and "The Forest Lover" is lushly rich with detail. Vreeland's Emily is brash and unafraid, a strong woman who knows what she wants and works to get it. Emily's friend Sophie is a heartbreaking character; be sure to read the Author's Afterword at the end of the book to learn about the life of the real Sophie Frank. Also take a good look at the cover of the book. Yes, it's one of Emily Carr's paintings, and you'll find others inside the book, although "The Forest Lover" is a story that is a work of art in itself. by Terri Schlichenmeyer THE ATLANTA JOURNAL CONSTITUTIONIn 1912, a lady painter meets her true nature by Kaye Gibbons "The Forest Lover." by Susan Vreeland. Viking. $24.95. 331 pages. The verdict: An absorbing study of inner needs and external forces. When any of my daughters' teachers asks them to read a novel that is set in the great outdoors - "The Old Man and the Sea," "Moby Dick," anything by Willa Cather - a sort of agonized gloom washes over our home. They want to be good students and read these novels about winds blowing gently across plains, and I want to be a good parent and make them. I want to tell them that five pages of natural description, odes to sunrises and sunsets, prairies, moors, ice storms, could never be tedious if they're well-written. I want to tell them that they should engage their minds in human drama even if it isn't set inside the house or around the yard. But I don't. I can't. They know I'll load them up and haul them off to buy Cliffs Notes, hoping that the trip will be all the outdoor life we will have to endure that day. They know I'll sympathize because they know the only thing I dread more than reading natural description is writing it. They hear the moans when I feel pressured to write more than, "The sun set. It was dark for hours. The sun rose." The frustration to say more can be acute, but after seeing the way Stephen Crane described the sun as a "red wafer," pulling literal and metaphysical meanings together in one lasting, brilliant image, I figured there wasn't much left worth saying on the subject of nature in general. And then, Susan Vreeland, best-selling author of "The Girl in Hyacinth Blue," "What Love Sees" and "The Passion of Artemisia," produces her latest novel, "The Forest Lover," and it becomes instantly clear that reading about the natural world doesn't have to be boring, tiring or repetitive. Frankly, the title had been enough to drive someone with this kind of exteriors neurosis away, but dread falls away immediately when Vreeland introduces her protagonist, Emily Carr, an underappreciated yet influential painter she brings to life not only in the wild forests on the western coast of Vancouver Island, but in Paris art studios where she studies for a year, and in provincial, stultifying drawing rooms where her art and ambition are ridiculed and dismissed by her family. Vreeland follows Emily, who lived from 1871 to 1945, as she goes into territory rarely visited by white people without the motives to proselytize or industrialize. She is not a missionary; her only mission is to paint indigenous people, to document their lives - most notably, the totem poles that she knows to be on the verge of disappearance. Lacking financial support and what Edith Wharton once described as a sort of spiritual encouragement from both the local artistic community and her family, Emily uses the small trust left by her tyrannical, horrifically critical father to travel to Paris, where she suspects she'll find an atmosphere more conducive to "lady painters." There she hopes to absorb some of the intense artistic energy of the day and learn to use the bold new methods of men like Matisse before she returns to Vancouver and goes back into the forest to paint everything she can before it's all gone. Her private studio instruction frequently contains lessons that would be just as valuable to a writer, as when she is told, "You paint more than the scene. You paint into it what's in your mind." When she returns to Vancouver and displays the same work she has had hung at the Grand Palais as well as her newest forest paintings, any hope for approval in British Columbia, her "heart's home," is dashed by reviewers who say she was a nice enough lady painter before Paris, but now, "she exhibits only the work of an agitated imagination." One of Vreeland's best, most economical accomplishments is showing the painter's vulnerability and inner need for acceptance underneath her brave, stoic refusals to be wounded. Although the road to acceptance is long and often bitterly lonely, there are a few people who do understand along the way, and they are finely drawn, with pitch-perfect voices. When Emily Carr does "make it," as far as the time and place will allow, it is the humble voices of a basket maker with 13 children, a fur trader with no use for modernity, and a friend named Harold whose sanity abandons him when he goes too deeply native, that remain the most urgent and joyful in the life of the painter and in the novel. They are ordinary voices telling an extraordinary woman that she mattered all along, that she was already somebody - a vital lesson for a lady painter in 1912, as well as for a lady writer in 2003. |

|

|

|

|