|

Ochre: Bright Earth at its Source

|

|

|

|

Limonite: iron oxide.

|

|

|

When gold mixes with blood, the legend goes,

And when the sun slants low, the bright earth glows.

|

|

|

Image©

Marcia M. Mueller

|

|

|

|

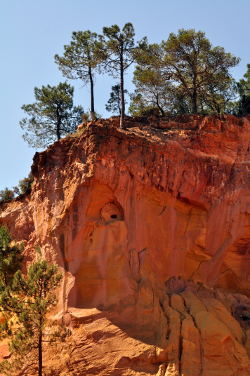

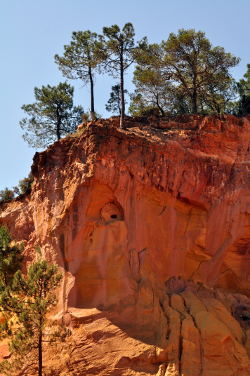

Ochre Cliffs: Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

In most places of Provence where chalky white limestone is the bedrock of the landscape, the ochre of the mountainous Vaucluse within Provence is a stark contrast, a fantasy, an enchantment. In a broad vein spread over twenty-five kilometres in the heart of the Vaucluse, the hues of ochre come and go of their own free will, and change with the time of day and the season.

|

|

|

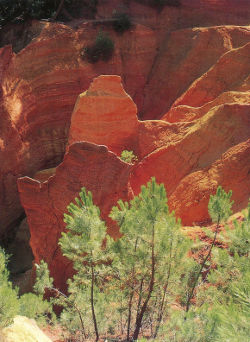

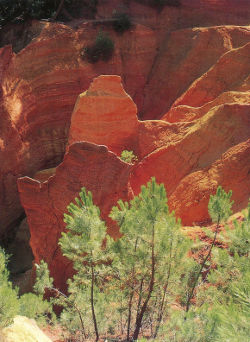

Labyrinth of "Le Sentier des Ocres," the Path of Ochres, Roussillon

|

Dazzling the eye under the bright sunlight of the South, they become saturated in intensity when rain penetrates the surfaces of the cliffs and stuccoed houses. That was how it was the first time I saw Roussillon, in a day-long drizzle. That was how it was when I knew I would write this novel.

The oldest pigment in the world, used in this region since prehistory, has given rise to legends that blood and gold mixed together and streamed, molten, down the cliffs. It's actually constituted of billions of imperceptible particles that reflect light, each in its own fashion. Ochre is more than a color. It is a vibration, and that's what associates it with quivering life.

|

|

|

|

Stairs to "Le Sentier des Ocres": Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

The ochre canyons of Roussillon are a spectacle of nature and man. Mistral winds ripped away vegetation from ochre cliffs; quarrymen with picks released chunks, leaving grooves in the stone that catch the light; more winds carved the walls into sinuous alleys and left pinnacles.

|

|

|

Susan Taking Notes:

Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

Now Le Sentier des Ocres is a fantasy gallery of spires, swirling walls with names such as Path of Giants, Tooth of the Wolf, Circle of Needles, Valley of Fairies.

|

|

|

Susan in "La Sentier des Ocres" Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

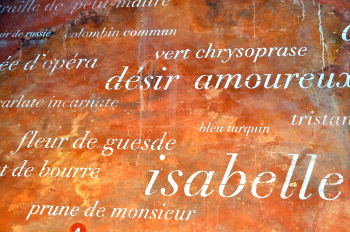

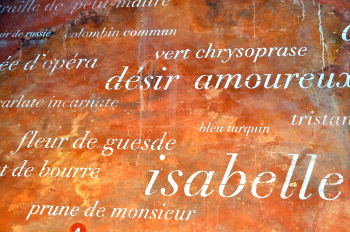

The history of ochre began around ten million years ago when the sea mixed ochreous sand containing the mineral glauconite rich in iron hydroxide and kaolinite which combined with various measures of limonite, goethite and hematite to form the colors we see on Roussillon's cliffs today. The palette of ochres of the Vaucluse extends from cream and the palest yellow to egg yolk yellow, through all the oranges and salmon and rose, to a bright brick red and even purple.

|

|

|

Names of Pigments: Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

In the Region of Apt wherein Roussillon lies, the mining of ochre began in Paleolithic times, but in 1785 in Roussillon, Jean-Etienne Astier was the first to manufacture the ore as a colorant and thickener, and in 1848, the exploitation began in Gargas as well.

|

|

|

The Bruoux Mines, Gargas, Interior

|

The ochre quarries and mines flourished, with some 2,000 men employed in the industry. Quarries and washing sites dotted the region, and 40,000 tons of ochre were produced. Of this, 90% of the refined ochre was exported. The use in artists' colors was relatively limited compared to its industrial uses in the manufacture of house paint. Unalterable by centuries of light, resistant to corrosion, it's a marvelous substance.

Other products include coatings on metal and a thickener in the manufacture of linoleum and rubber. Look at the rubber ring in the lid of a canning jar. One constituent is ochre. It's also used in the making of paper, cardboard, pharmaceutical and cosmetic products.

|

|

|

Interior of "L' Usine Matthieu," the Matthieu Ochre Works, Roussillon:

Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

In 1929, the mining of ochre declined, and decreased by half in 1938 with the wartime closing of foreign markets, but it wasn't until 1971 that the mines stopped producing entirely. However they have reopened, and in this revival, 1,300 tons are produced annually.

I'll let an excerpt from the novel explain the process:

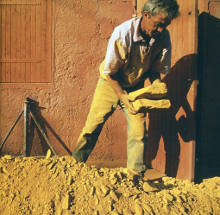

As we walked through a forest of oak trees, he explained that the ochre ore, quarried or mined, had to be separated from sand. It was ninety percent sand and ten percent pigments, he said. Chunks of the same color were first flushed with water that ran through large diameter pipes.

|

|

|

"L'Usine Matthieu" with pipe: Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

Managing the flow of water was done by boys called washers.

"There used to be twenty such factories and a thousand ochre workers and miners in the area."

Every pipe we saw had once emptied into its own narrow concrete canal, and for every canal, lower down the incline, there were several different levels of large rectangular concrete basins, some of them now cracked and overgrown with weeds.

|

|

|

|

Ochre Drying Basins: Image© Marcia M. Mueller

|

"They are decantation beds. A flux of ochre, sand, and water is sent through the pipes to the canals and basins. The sand is heavy and settles quickly, while the ochre in suspension flows down the canals into the basins. At night, when the water is still, the ochre settles at the bottom. In the morning, the water on the surface is released through small locks. In this way, the basins are filled with successive layers of ochre. When the ochre attains a thickness of fifty centimeters, no more water mix is allowed in and the ochre remains in the basins for six months in order to dry.

|

"Then it is cut into bars and sent to the furnaces to refine the colors by heating them at various temperatures for different lengths of time."

|

Marcia M. Mueller, the fine art photographer whose work you see here is offering for sale a special 2015 Lisette's List calendar. Find out more by visting www.MarciaMueller.com

|

|