|

Two Friends, Two Painters

Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne

|

|

|

|

With the acerbic wit of both painters tinged with disappointment, Pissarro referred to the Impressionists as "the dear unwanteds," Cézanne as "the great criminals of Paris."

|

|

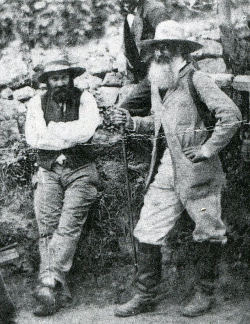

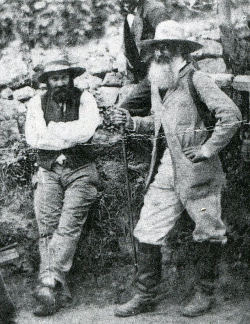

Paul Cézanne (left), Camille Pissarro (right)

|

Their opinion of each other was quite another thing. Cézanne called Pissarro "the humble and colossal Pissarro" and "the great Pissarro, my master," and "mon bon Dieu, Pissarro,"and Pissarro, who foresaw that Cézanne would lead painters to a new aesthetic, said of Cézanne, "He was influenced by me and I by him."

As for the critics of their time, they were, to say the least, ungenerous. Léon de Lora wrote in Le Gaulois, April 10, 1877, "There is no way to figure out Monsieur Cézanne's "Impressions d'après nature; I took them for palettes that had not been cleaned....But Monsieur Pissarro's landscapes are no more legible and no less prodigious. Seen close up, they are incomprehensible and awful; seen from afar, they are awful and incomprehensible."[1]

|

With the benefit of 150 years, we see what the critics, with their prejudices and fears, refused to see. And we see the results of the two painters' strivings as having enriched and forwarded European painting enormously. They taught us that shadows are not black or gray, but blue and purple and green; that shapes can be seen and appreciated in their geometric simplicity; that brushstrokes are not to be hidden and smoothed as in the Renaissance, but glorified, whether they are mere touches and dabs or long, broad strokes declaring that there was a painter here standing before his easel, an individual who reacted to what he saw in this way.

|

Camille Pissarro: Leading Spirit of

"The Dear Unwanteds" (1830-1903)

|

|

|

|

|

|

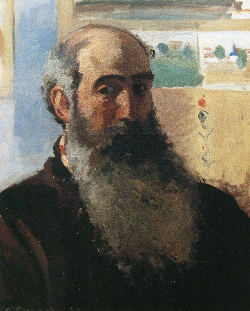

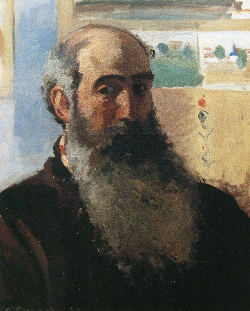

Pissarro self-portrait

|

Dealer Durand-Ruel described Pissarro's paintings as "The world in situ. You make me feel as though the world is good." It was either Durand-Ruel or I who wrote that his "paintings have God in them."

In a review of the Impressionists show of 1877, critic Ernest Fillonneau wrote in Le Moniteur des Arts, "Monsieur Pissarro is becoming completely unintelligible. He puts together...all the colors of the rainbow; he is violent, hard, brutal. From an effect which might well have been acceptable, he makes something unbelievable."[2]

Despite such invective, Pissarro was faithful to his work and to his fellow Impressionists. He encouraged them, kept them painting when they were on the verge of giving up. All of them in this painting fraternity looked to Pissarro. He was a constant stabilizing factor, never missing showing his work in any of the eight Impressionist shows, even when the group was splitting apart and the need for their solidarity lessened as they were slowly becoming accepted.

|

|

|

|

Pissarro, Le Verger, The Orchard

|

In his days of poverty during coldest, rainiest months, Pissarro and his burgeoning family lived in a cramped apartment on boulevard Rochechouart at the base of Montmartre, and he painted in friends' studios. Despite excruciatingly hard times, this brave man painted on, standing absolutely still as a tree on a windless day, at one with his canvas, adoring the scene before him, anointing it with his loving touches.

"I love the stone houses, even the pigeons dumping on the tile roofs, the pattern of cultivated fields and wild ones, patches of different colors, the scattering of mills and smokestacks, the smell of this earth, even good, healthy manure. I belong here as much as the Viosne stream, which runs to the Oise, then to the Seine, and to the sea. Everything is connected here, that orchard offering its fruit to generations, that river that quenched the thirst of Romans, even of Celts. I am a part of them now; they are a part of me. Isn't there a hunger in every human being, painter or not, to find a place in the world that gives to him so richly that he wants to honor it, give back--that's it--give back--that's what I'm doing. That's what makes me feel good at the end of each day."

|

|

|

|

Pissarro, The Cabbage Harvest, L'Hermitage, Pontoise, 1875. Cincinnati Art Museum.

|

Still peddling paintings at 48 years old without a gallery to show his work, he turned despair into fortitude for the sake of his wife Julie and their seven children.

At sixty years old, Pissarro's paintings sold well, but in 1889, he had an eye infection. It could have been seen as a disaster because it prevented him from painting outdoors. He adjusted, gave up his rural milieu, and painted street scenes in Paris from hotel room windows. Bless him; he never lost faith.

|

[1] and [2] T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life.

|

|

Paul Cézanne: Precursor of Modernity among "The Great Criminals of Paris"(1839-1906)

|

|

|

|

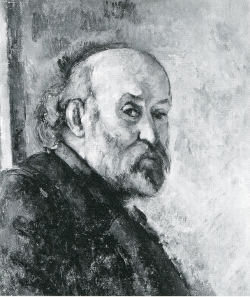

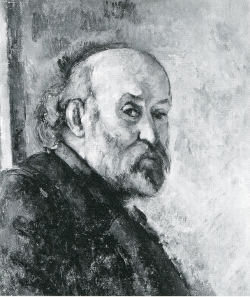

Paul Cézanne Self-portrait

|

|

|

Paul Cézanne standing

|

|

Nothing came easily to Cézanne. His method of working demanded deep meditation. He constantly struggled to attain a visual and emotional profundity, and battled with every stroke, all the while sticking firmly to his principles, declaring, "The labor which brings about progress in one's own calling is sufficient consolation for a lack of comprehension on the part of fools." I love that fortitude.

Having been born in Aix en Provence where he had no art training, he was fortunate to meet the Impressionist painters through his school friend, Émile Zola. Pissarro encouraged him to abandon his violent, naturalistic style inspired by Courbet and Delacroix, and adopt the lighter colors and softer techniques of the Impressionists.

Although he painted figures in situ--card players and bathers--and contemplative portraits of country folk, his painting world consisted primarily of the countryside around Aix--including seventy-five landscapes (thirty oils, forty-five watercolors) with Montagne Ste-Victoire in the background, as well as farmhouses and cabanons--and the Mediterranean near Marseille at l'Estaque. Without seasonal cues, largely without figures, they convey timelessness.

|

"Our native soil," he said, "so vibrant, so harsh, and so reverberant with light that your eyes squint and your vessels of sensation are enchanted...[I feel] enormous affection for the contours of my countryside...The sun is so startling that it makes it look as if objects could be lifted off in their outlines, which are cast not just in black or white, but in blue, red, brown, purple."

|

|

Cézanne, La Carrière de Bibémus, (The Bibémus Quarry) Museum Folkwang, Essen

|

He abandoned perspective as it had been carefully worked out by Renaissance painters. Instead, he conveyed space by overlapping of planes and emphasizing their forms over texture. From this freedom, he moved toward rendering objects in their simplified, geometric forms, using gradations of color as a means for modeling shapes. He strove to make every stroke distinct so as to define a plane, making his structure more abstract than any seen by painters before him. In this way, he imbued his shapes with spirituality, that is to say, spiritual substantiality.

|

The more he worked, the more the work removed itself from the original subject and approached abstraction, pure design. His hard-won development of these principles became the basis for Cubism. It was no less than a major turning point in western painting.

He belonged less to the Impressionists than did Pissarro. He was not at all interested in portraying the parade of bourgeois society enjoying picnics, dancing, drinking, boating, strolling on Parisian boulevards. His milieu was the structure of the earth, silent and grave, and of smaller, humbler things, rustic pottery, sculls, fruit.

|

|

Cézanne, Apples and Biscuits, Musée de lOrangerie, Paris

|

|

In fact, he found more holiness in painting fruit than in painting flowers or women. He revived the classical still life, giving it his own brand of more humble Provençal truth. "People think a sugar bowl has no physiognomy or soul... you have to...cajole them, those little fellows. These glasses, these dishes, they talk among themselves. They whisper secrets. I gave up on flowers. They fade too quickly. Fruits are more faithful."[3]

Whereas the Impressionist bathes everything in innumerable, vibrating touches dancing off in all directions, Cézanne's strokes are ordered, firm, stable. Of his practice of letting his brush strokes show, dealer Durand-Ruel called this "the triumph of living art over academic art. Not clever, not smooth. [It was] rough and true." Painting was a physical act for him, involving excessive corrections which suggest an intensity of experience. He must have been exhausted after a day in front of a canvas.

"We hardly dare say that Cézanne lived; he painted...His painting estranged him from the course of life,"[4]

Consequently, it is no surprise to hear him say, "Art is a religion. Its goal is the elevation of thought."

I fully agree.

Such courageous, enduring, visionary men they were. I'm grateful for the chance to honor them in my novel.

|

|

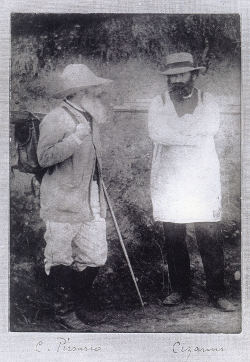

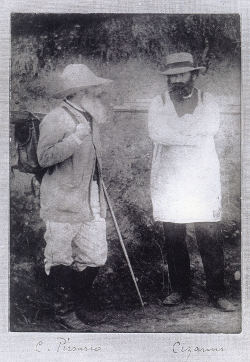

Camille Pissarro (left), Paul Cézanne (right)

|

|

[3] and [4] Michael Dean, editor, Conversations with Cézanne

|

|